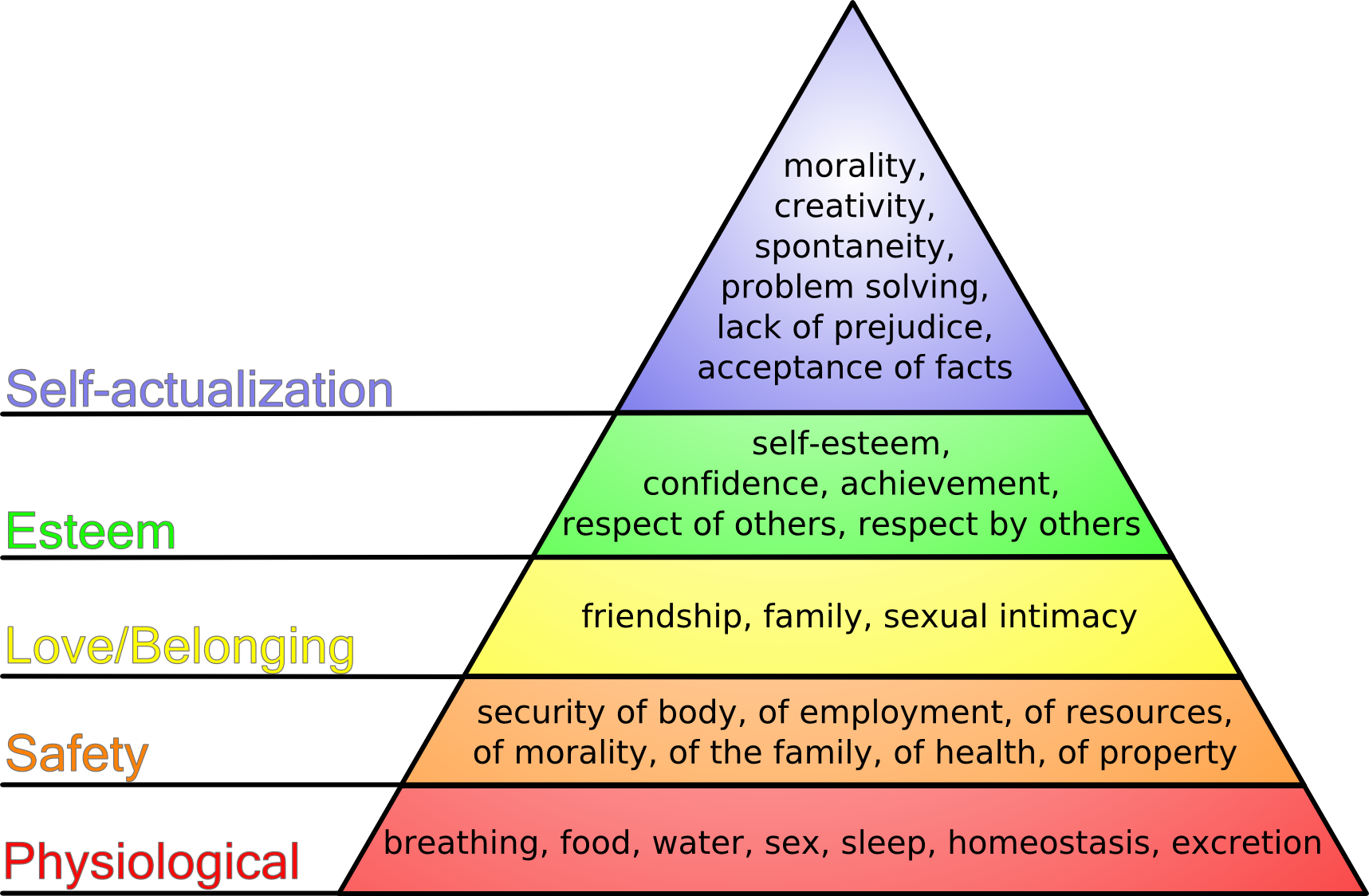

Abraham Maslow introduced the term Jonah Syndrome, at the suggestion of Frank E. Manuel, in 1968 in the journal Religious Humanism, changed to Jonah Complex in his posthumously published book Farther Reaches of Human Nature, in the chapter on ‘Neurosis as a Failure of Personal Growth’. Maslow was much concerned by the fears that inhibit us from reaching out to our fullest potential as humans, at the peak of his famous hierarchy of needs, which he called ‘self-actualization’.

Abraham Maslow introduced the term Jonah Syndrome, at the suggestion of Frank E. Manuel, in 1968 in the journal Religious Humanism, changed to Jonah Complex in his posthumously published book Farther Reaches of Human Nature, in the chapter on ‘Neurosis as a Failure of Personal Growth’. Maslow was much concerned by the fears that inhibit us from reaching out to our fullest potential as humans, at the peak of his famous hierarchy of needs, which he called ‘self-actualization’.

Jonah’s hesitation to speak “the word of the Lord” against the wickedness of Nineveh was symbolized by his being eaten by “a great fish” before he eventually went there to fulfil his destiny. Using this allegory, Maslow began his article with these words:

All of us have an impulse to improve ourselves, an impulse toward actualizing more of our potentialities, toward self-actualization, or full humanness, or human fulfillment, or whatever term you like. Granted this for everybody, then what holds us up? What blocks us? … In my own notes I had at first labeled this defense the “fear of one’s own greatness” or the “evasion of one’s destiny” or the “running away from one’s own best talents.”

He then goes on to say:

We fear our highest possibilities (as well as our lowest ones). We are generally afraid to become that which we can glimpse in our most perfect moment, under the most perfect conditions, under conditions of greatest courage. We enjoy and even thrill to the godlike possibilities we see in ourselves in such peak moments. And yet we simultaneously shiver with weakness, awe, and fear before these very same possibilities.

These limiting fears can arise both within us as individuals and within the society in which they occur. First, examining why peak experiences are most often transient, Maslow writes:

We are just not strong enough to endure more! It is just too shaking and wearing. So often people in such ecstatic moments say, ‘It’s too much,’ or ‘I can’t stand it,’ or ‘I could die.’ … Yes, they could die. Delirious happiness cannot be borne for long. Our organisms are just too weak for any large doses of greatness. … Does this not help us to understand our Jonah syndrome? It is partly a justified fear of being torn apart, of losing control, of being shattered and disintegrated, even of being killed by the experience.

So sometimes when we let loose the unlimited potential energy of Intelligence and Consciousness, the effect can be overwhelming, leading to what Christina and Stanislav Grof call a spiritual emergency, when Spirit emerges faster than the organism can handle. We can even fear success, even fear God, in whatever way we view Ultimate Reality, ranging from Buddhist Emptiness (Shūnyāta) to the Supreme Being of the Christians. As Ernest Becker writes in The Denial of Death, “It all boils down to a simple lack of strength to bear the superlative, to open oneself to the totality of experience.”

It was not only the writers of the Old Testament who were aware of the Jonah syndrome. Arjuna had a similar experience, recorded in the Bhagavad Gita. When Krishna showed him the Ultimate Cosmic Vision—“all the manifold forms of the universe united as one”—Arjuna said, “I rejoice in seeing you as you have never been seen before, yet I am filled with fear by this vision of you as the abode of the universe.”

Elaine Pagels makes a similar point in Beyond Belief, the quotation in this passage coming from the sayings of Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas:

Discovering the divine light within is more than a matter of being told that it is there, for such a vision shatters one’s identity: “When you see your likeness [in a mirror] you are pleased; but when you see your images, which have come into being before you, how much will you have to bear!” Instead of self-gratification, one finds the terror of annihilation. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke gives a similar warning about encountering the divine, for “every angel is terrifying.”

Maslow points out that there is another psychological inhibitor that he ran across in his explorations of self-actualization:

This evasion of growth can also be set in motion by a fear of paranoia. … For instance, the Greeks called it the fear of hubris. It has been called “sinful pride,” which is of course a permanent human problem. The person who says to himself, “Yes, I will be a great philosopher and I will rewrite Plato and do it better,” must sooner or later be struck dumb by his grandiosity, his arrogance. And especially in his weaker moments, will say to himself, “Who? Me?” and think of it as a crazy fantasy or even fear it as a delusion. He compares his knowledge of his inner private self, with all its weakness, vacillation, and shortcomings, with the bright, shining, perfect, faultless image he has of Plato. Then of course, he will feel presumptuous and grandiose. (What he fails to realize is that Plato, introspecting, must have felt the same way about himself, but went ahead anyway, overriding his own doubts about self.)

Of course, such fears arise from the egoic mind, afraid of what those defending the status quo might think of how you think and behave. However, once we reach our fullest potential as Gnostic Panosophers, all problems and solutions cease to exist, for Wholeness is the union of all opposites. Under these circumstances, all we can do is follow the Divine energies arising within us, trusting in Life that any practical ‘problems’ will be solved as evolution unfolds. Nevertheless, we also need to bear in mind that Edward de Bono said in The Use of Lateral Thinking “In general there is an enthusiasm for the idea of having new ideas, but not for the new ideas themselves.”

This brings us to another aspect of the Jonah Syndrome. From the point of view of society, Maslow points out, “Not only are we ambivalent about our own highest possibilities, we are also in a perpetual … ambivalence over these same highest possibilities in other people,” which he calls ‘counter-valuing’. As he goes on to say,

Certainly we love and admire good men, saints, honest, virtuous, clean men. But could anybody who has looked into the depths of human nature fail to be aware of our mixed and often hostile feelings toward saintly men? Or toward very beautiful women or men? Or toward great creators? Or toward our intellectual geniuses? … We surely love and admire all the persons who have incarnated the true, the good, the beautiful, the just, the perfect, the ultimately successful. And yet they also make us uneasy, anxious, confused, perhaps a little jealous or envious, a little inferior, clumsy.

In Scandinavia, this ubiquitous counter-valuing tendency has been encapsulated in a cultural law, called Jantelagen (the law of Jante), a concept created by the Norwegian/Danish author Aksel Sandemose in his novel A Refugee Crosses His Tracks in 1933. The novel portrays the small Danish town Jante, modelled on his hometown, where Janters who transgress an unwritten ‘law’ are regarded with suspicion and some hostility, as it goes against communal desire in the town, which is to preserve social stability and uniformity. In essence, this law states that no one is special or better than anyone else.

Jantelagen, lying deep in the Scandinavian subconscious, is a rather ambivalent philosophy. For while it can lead to social stability and harmony, it actually inhibits people from realizing their fullest potential as human beings. Like the story of six blind men who seek to know what an elephant is, it is only permitted to see the elephant from the perspective of the tail or the trunk, for instance. To see the elephant as a whole is not allowed, for this would make anyone with such a Holoramic perspective special and hence unacceptable, a clear sign of counter-valuing.

The Jonah Syndrome is a particularly sensitive issue for anyone seeking to use Self-reflective Intelligence to heal their fragmented mind and split psyche in Wholeness, thereby finding great joy in solving the ultimate problem in human learning. Some have said that such an awakening, liberating endeavour is hubristic, grandiose, messianic, and preposterous, an act of self-aggrandizement and megalomaniacal madness. These include Bernard Williams, referring to René Descartes, Joseph Brent, referring to Charles Sanders Peirce, and Martin Rees and Henryk Skolimowski, referring to physicists’ attempts to develop a Theory of Everything (TOE) or Grand Unified Theory (GUT).

Jung was well aware of this tendency, calling it psychic inflation, meaning “an extension of the personality beyond individual limits, … a phenomenon … [that] occurs just as often in ordinary life [as in analysis].” For instance, when people “identify themselves with an office or title, they behave as if they were the whole complex of social factors of which that office consists. … L’état c’est moi is the motto of such people.”

For myself, I first became aware that I was suffering from the Jonah Syndrome in 1984, when a friend I met at the Teilhard Centre in London gave me this diagnosis of my psychological condition. In the event, it has taken nearly forty years of profound spiritual practice before I was sufficiently healed to venture out into the world with what I have learnt since I was seven years of age, when I set out to end the long-running war between science and religion.

Jonah is from Hebrew yônâ ‘dove’, from Semitic root ywn.

Syndrome, 1541, ‘a number of symptoms occurring together’, from medical Latin, from Greek syndromē ‘concurrence of symptoms, concourse of people’, from syndromos ‘a running together; place where several roads meet’, from syn- ‘with’, from PIE base *ksun-, and dromos ‘running, course, race’, from PIE base *der- ‘to run, walk, step’.